.jpg)

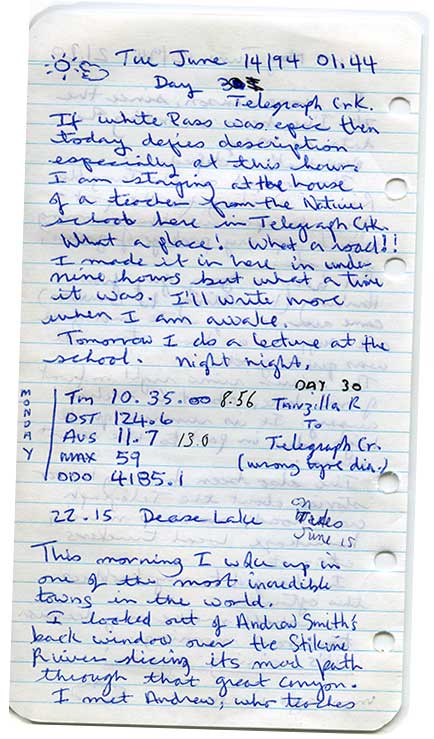

Hero Shot, Grand Canyon of the Stikine, June 13, 1994

When I snapped the “hero shot” above, I thought of myself as old and irrelevant.

Two years before, an ancient of 40, I’d fled the big city for the relative calm of Vancouver Island at the cost of business opportunity and diversity. Or perhaps I just couldn’t cut it in the Big Smoke.

Mustering what remained of my photographic and adventure credentials, I attracted sponsors — Kodak Canada, Rocky Mountain Bicycles, Jandd Mountaineering, Mountain Safety Research/Walrus — for what I imagined might be my last great hurrah. On May 15, 1994, I roused myself from a winter of discontent, deserted another nascent photography business, not to mention my patient wife, and pointed my bicycle north to Alaska.

Here’s the unexpurgated story from one day of my solo, two-month odyssey in search of myself.

.jpg)

Beautiful British Columbia Traveller | Summer 2000 edition

BLAAAM! Clacka-clacka-clacka. Uh-oh. That’s not a sound a cyclist wants to hear while pedalling in the remote northwestern reaches of British Columbia. I look back at my rear tire: it’s popped off the rim and the tube is in shreds. So much for the extra few pounds of pressure I’d squeezed in at the service-station, hoping to combat the increased rolling-resistance of fat treads I’d put on for rougher roads ahead.

Lucky for me, I’ve just rolled off the blacktop near Dease Lake (pop. 700), the largest community on the Stewart-Cassiar Highway and a service and supply centre for the region. I install my spare and duck into Chico’s Repair Shop, Ltd., hoping for a patch-up. I’m beginning to wonder if I haven’t taken on a little too much adventure, detouring off Highway 37, down the narrow, 113 kilometre strip of dirt known as the Telegraph Creek Road. Earlier in the morning, at my camp on the storm-swollen Tanzilla River, I’d debated whether to take this long side trip to the historic gold-rush town of Telegraph Creek.

I’ve been on the road for a month already: cycling north from Nanaimo to Port Hardy; ferrying to Skagway, Alaska; cycling north to Whitehorse, Yukon; then east to intersect Highway 37. Heading south now, on the Stewart-Cassiar, I still have a good chunk of this 750 kilometre patchwork of gravel and bumpy pavement to ride, plus the lengths of highways 16, 97, and 99 to reach home. But having come all this way, how could I resist this wild side road, following first the Tanzilla River out of Dease Lake, through the Grand Canyon of the Stikine, along the border of Mount Edziza Park to Telegraph Creek? I couldn’t!

“There you go bud — Good as new!” Chico Klassen has glued the special valve, cut from my exploded tube, onto a slightly used one, fished from a barrel in the attic. Genius.

“That’s great, man. Thanks!” I enthuse. “How much do I owe you?” The resourceful mechanic waves his hand dismissively.

Klassen is the kind of practical, no-nonsense personality common to the North. He came to the Cassiar country with a diamond driller’s ticket, but never made it past Dease Lake. Rather than working in the mining industry, he has built a cosy little repair business here, in the largest community on the Stewart-Cassiar Highway. He expects you to accept his common-sense assistance, then get out of his harried way.

I stop in at the Dease Lake post office to pick up the supply parcel mailed by my wife. From the selection of instant noodle dinners, powdered milk, tea-bags, coffee, oatmeal, granola bars and film, I cram a few days supplies into my panniers.

Across the street, the blocky, government building that holds the local RCMP detachment appears as a bastion of civic orderliness amongst the town’s typical architectural anarchy. It also appears a likely place to store the rest of my provisions.

“There’s twenty-percent grades in there, y’know,” Sergeant Mason Dodds warns of the Telegraph Creek Road. “You’ll be doing some walking.” I’ve never walked a bike in my life — not on thigh-crippling Jackass Mountain in the Fraser Canyon, not on the Kootenays’ 1,189-metre Monashee Pass. “I rode over White Pass out of Skagway two weeks ago,” I boast. Dodds just smiles.

“Keep your ears open for trucks; the locals drive that road pretty fast. Watch out for blind corners, too. Some of those cliffs drop 400 feet into the canyon — straight down.”

Leaving the last few straggling houses behind, the road follows the river across the Tanzilla Plateau, through an old burn. The first 40 kilometres pass quickly under my tires.

Sweating up an 8-percent climb, I look forward to a fast decent. At last, the hill tops out. I launch my chrome-molybdenum Rocky Mountain Blizzard into space, dodging potholes and picking up speed. As I dive into a steep bend, the bike’s momentum slings me up a gravel bank toward a deep ditch. By throwing my full weight off the saddle to the inside like a racing motorcyclist, I manage to cling on the lip of the curve, just shy of disaster.

Easing on the brakes on a wood-decked bridge over a splashing creek, I punch the little white “mode” button on my computer until it displays the maximum speed function. It reads: 59 km/h. From now on, I vow to get by on less adrenaline.

Time to find a lunch spot. I detour up a narrow path bordered by thick brush to a grassy bluff. The threshold affords an expansive view of the Tuya River far below, snaking through a steep-walled valley to its junction with the Stikine. To the south, thrusting above a gentle, wooded ridge, the snowy volcanic cone of 2,787-metre Mount Edziza plays havoc with my camera’s light-meter.

A sudden rustling draws my attention to the meadow dropping away behind me. Bear? No. A bay stallion breaks out from the trail, followed by his equine entourage. He announces his dominion over this territory with a loud, convincing whinny and pawing in the dust.

Lunch is over. I leap on my bike and plunge back down the slope. The only way out is directly through the wild horses. At the last possible moment, the stallion yields the game of chicken to me. His herd scatters as I career down the track and back onto the road.

Like a parted liquid, the horses flow in behind me, bursting through the hedge in hot pursuit. But on the downhill gradient I quickly outrun the excited herd, left here to range, I discover later, by the Tahltan guides of Iskut, a 350-person community to the south. A long straight stretch lies ahead, and I soon relax into a hypnotic cadence.

A weak sun sulks behind woolly clouds and the atmosphere is close and muggy as I pedal toward the Grand Canyon of the Stikine. Too soon, the gentle plateau gives way to a more uneven landscape. Several times over the next 30 kilometres I must concede to Sergeant Dodds, dismounting to push my overloaded bike, like an obstinate mule, up a 20-percent grade.

At the next viewpoint, though, fatigue evaporates. Beyond the cliff edge, the ruddy walls of the Stikine canyon split the viridian countryside from east to west like a gigantic moat. Here, the driest part of the Yukon-Stikine Highlands clearly exhibits the effect of the Coast Mountains’ rain shadow: scattered woods breached by grassy, whaleback ridges, tufted with fragrant juniper. With this wild scene as a backdrop, I set up my little tripod for the obligatory “hero shot” on the arid precipice.

Afterward, I continue down the zigzag switchbacks that twist to the valley floor. Sweeping around the tight turns, a warm breeze lifts my cap.

“You idiot!” I berate myself. “Where the fuck is your helmet?”

I abandon my bike on the side of the road to jog back out of the valley. The helmet — doffed as an indulgence to vanity during my self-portrait session — sits, where I’d left it, on the garbage can, back up at the viewpoint.

Half-an-hour later, with my helmet and a modicum of humour retrieved, I continue toward the confluence of the Stikine and Tahltan rivers. My enjoyment is brief, as suddenly I realize my cycling tights have gone missing from under my rear pannier flap.

Just then, a car emerges from a thick cloud of ochre dust. I wave them down. A petite woman with a skewed tower of bleached-blonde hair rolls down the window. “Excuse me. I’ve lost my tights back there somewhere,” I tell the incredulous couple. They lean toward me in unison, as if confronting a hallucination. “If you happen to find them, could you drop them at Chico’s Repair Shop in Dease Lake?

“You realise what you’re in for up there?” the well-coifed passenger inquires.

“I’ve made it this far,” I volunteer, hopefully.

“Sooner you than me!” pities the hairdo, and off they roar.

I press on, following the road over a fifteen-metre-wide ridge of corrugated lava, approaching the ancestral native village of Tahltan. It’s clear what had unnerved the couple. Perilous, 120-metre drop-offs plunge into the giddy chasm of the Stikine on one side, and the Tahltan River on the other. But the views are breathtaking.

Below at Tahltan, a monumental cliff looms above the turgid waters of the river. Like some enormous heraldic crest, the layered volcanic rock forms the outstretched wings of a colossal eagle, as if swooping to pluck a salmon from the current.

In July 1838, Robert Campbell, the first white man to explore the area, described the scene here, viewed from the canyon rim. “Such a concourse of Indians I had never before seen assembled. . . . [They] camped here for weeks at a time, living on salmon which could be caught in the thousands in the Stikine by gaffing and spearing, to aid them in which the Indians had a sort of dam built across the river.”

It was much the same forty-one years later, when American adventurer John Muir sojourned here.

“At the confluence of the first North Fork of the Stickeen,” he wrote, “I found a band of Toltan or Stick Indians catching their winter supply of salmon in willow traps, set where the fish are struggling in swift rapids on their way to the spawning grounds. A large supply had already been secured, and of course the Indians were well fed and merry. They were camping in large booths made of poles set on end in the ground, with many binding cross-pieces on which tons of salmon were being dried. The heads were strung on separate poles and the roe packed in willow baskets, all being well smoked from fires in the middle of the floor. The largest of the booths near the bank of the river was about forty feet square. Beds made of spruce and pine bows were spread all around the walls, on which some of the Indians lay asleep; some were braiding ropes, others sitting and lounging, gossiping and courting, while a little boy was swinging in a hammock. All seemed to be light-hearted and jolly, with work enough and wit enough to maintain health and comfort.”

I tackle the climb alongside the yawning void. Each painful revolution of my lowest gear gains a few more inches above the white, surging rapids that make this section of the great Stikine quite unnavigable, except by the odd adrenaline-crazed kayaker. Across the ravine, a steep, striated volcanic plug in 232,702 hectare Mount Edziza Provincial Park glows fiery red, ethereal in the evening light.

Though the thought seems heretical in view of this natural treasure, the potential electric generating capacity of the powerful waters raging below is not lost on B.C. Hydro. The corporation has spent $40 million on feasibility studies, for a series of dams on the Stikine and the adjoining the Iskut River. Here and there, along the canyon rim, white markers represent the water level, should the project ever proceed. In effect, this gorge would disappear, along with the teeming runs of Stikine salmon.Though plans for the project have fallen by the wayside in recent years, thanks to lobbying efforts by groups like “Friends of the Stikine,” and the river’s provincial heritage designation in 1997. Nevertheless, in this steep chasm, the Stikine will always appear to hydroelectric engineers as “a river made to be dammed.” This, along with threats from mining and logging activity, keeps the Iskut-Stikine system high on the Outdoor Recreation Council’s list of B.C.’s 10 most endangered rivers.

The track finally lays back on a stretch turned mucky by a localised squall. Grit and clay rattle in my mudguards, as I grind along in a tired daze.

The track finally lays back on a stretch turned mucky by a localised squall. Grit and clay rattle in my mudguards, as I grind along in a tired daze.

“Hi, Could you direct me to the campground,” I inquire of a young couple walking beside the road. They introduce themselves as Joanne Przystawka, the district nurse, and Andrew Smith, teacher at the Tahltan school. “The nearest is the forestry campsite out at Six Mile,” they advise, peering out from tightly cinched hoods. We all adopt the “Yukon wave” to dislodge the persistent mosquitoes.

“Is there a place I might be able to pitch a little tent here?” I plead. “I’m Ray— I rode nine hours from Dease Lake today.”

“Tell you what,” Smith offers, “you can come over to my place. There’s room in the yard to put your tent. Just watch out for dog shit.” Excellent.

Przystawka extends a supper invitation and they leave me to unpack my tent. I stomp about in the long grass searching for a level area, my thrashing loosing expanding clouds of frenzied mosquitoes.

The view into the valley, though, from Smith’s clifftop yard, is unbeatable. Telegraph Creek’s aging buildings—some overcome by the demands of gravity—stumble down the bank. The road to lower town plunges over a wooden bridge, while a spur contours to the modern Tahltan First Nation subdivision, and Glenora, 20 kilometres downstream. Wider and gentler here, the river below ranges west toward the peaks of the northern Coast Mountains. The Stikine’s waters, swelled by countless rivers and streams, will travel another 260 kilometres west before spilling into the Pacific Ocean at Wrangel, Alaska.

During the gold rush, in 1898, the benches below saw some five-thousand prospectors and entrepreneurs flooding up from the Alaska Panhandle. Newspaperman W.F. Thompson, who had followed the boom and bust cycle of ore discoveries around B.C., launched the Glenora News from a tent that spring “to advance the interests of the All Canadian Route to the Klondike,” a circuit avoiding the American-controlled Chilcoot and White Pass routes. The Dominion government espoused big plans: a narrow-gauge Cassiar Central Railway and a wagon road, north to Teslin Lake.

But even as multitudes were pouring into Telegraph Creek and Glenora, political opposition forced the government to cancel the contentious project. “Losing the prospect of a railway means death to this enterprise,” W.F. Thompson lamented, as many weary fortune-seekers left in disgust. Some, whether foolish or hardy, determined to winter over and press on up the hellish Teslin Trail. Two-hundred-and-fifty kilometres of bug-infested swamp and tangled bush separated the miners from Teslin Lake and the waterways leading to the gold-fields of Dawson.

Sixteen-year-old Guy Lawrence and his father were among the hard-cores who dug in for the winter. Luckier than the frozen corpses discovered by the father-and-son team on their northward trek in February of 1899, they went on to mine for gold in Atlin.

Many of the best-laid-plans have come to naught in this ramshackle town. Even Telegraph Creek’s name represents a record of dashed hopes.

The Collins Overland Telegraph — started by the US Western Union Company thirty years before the gold rush — promised to link North America’s communication system with that of Europe, via Siberia. Already a strategic northern river port, Telegraph Creek was assured a place on the line. But in 1867, when it became clear that competitor Cyrus Field had beaten them to the punch with a successful transatlantic cable, Western Union abandoned the project, leaving caches of expensive equipment along the unfinished route, south to Hazelton, along the hard-won trail

The town would get a second chance to warrant its name, however. Late in 1899, the Dominion Telegraph and Signal Service received authorization from the federal government to push a line north from Quesnel to Atlin. Two years of backbreaking labour and a sizeable fortune completed the project, just in time for the end of the gold rush. With Guy Lawrence as one of its tireless linesmen, the telegraph functioned intermittently for another thirty years, until costly maintenance on the remote line led to its final demise.

In spite of modern satellite communications, there remains an air of glorious isolation and a reassuring sense of continuity here. The cloud-wreathed mountains gather Pacific moisture; the Stikine River carries its eternal glacial burden out to sea; each year salmon still return in abundance, and the Tahltan people gather beneath the great basalt eagle to harvest the river’s bounty.

“Hey Ray, want a beer?” calls Smith from behind his screen-door. I abandon my half-erected, one-person tent, crumpled over the unyielding, waist-high grass.

“Come on in; you might as well use the spare room,” he offers. He doesn’t have to twist my arm. I follow him to the kitchen where he pops a couple of cold ones. We click the foaming cans. “To the mighty Stikine,” we toast, “may she always run free.”