Highway 93 (Kootenay Hwy.)

“The mountains are calling and I must go ….” ~John Muir

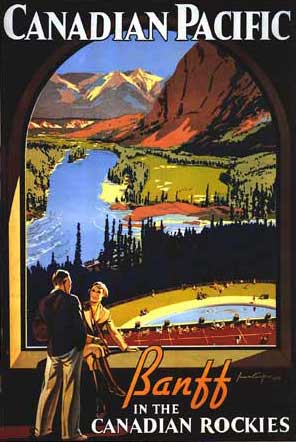

The magnificence of the Canadian Rockies has drawn tourists from around the world since the early days of European colonization. The steam train blazed the trail to tourism, with Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways mounting international advertising campaigns to lure wealthy visitors.

Building luxurious hotels, railway tycoons like William Van Horne, general manager of the CPR, imported Swiss mountain guides along with their dreams of turning the Rockies into a New World Tyrol.

In the late nineteenth century, a steady stream of Europe’s best climbers mounted expeditions to the Rocky Mountains, setting out from the terminus of Laggan Station (Lake Louise) to explore and ascend the great untrodden summits. British scientist Norman Collie, who first set eyes on the 325 km² Columbia Icefield from the summit of Mount Athabasca (with partner Herman Wooley) in 1898, visited 6 times, recording 21 first-ascents.

In the late nineteenth century, a steady stream of Europe’s best climbers mounted expeditions to the Rocky Mountains, setting out from the terminus of Laggan Station (Lake Louise) to explore and ascend the great untrodden summits. British scientist Norman Collie, who first set eyes on the 325 km² Columbia Icefield from the summit of Mount Athabasca (with partner Herman Wooley) in 1898, visited 6 times, recording 21 first-ascents.

By the early years of the 20th century, this corrugated, cordilleran backbone had become the scene of some of the greatest ascents of the day.

Arnold Louis Mumm and his faithful partner Moritz Inderbinen, Douglas William Freshfield, G. E. Howard, Geoffery Hastings, James Outram, A.O. Wheeler, with journalist Elizabeth Parker, co-founder of the Canadian Alpine Club, Albert H. McCarthy and Austrian Guide Conrad Kain (these two recording the first verifiable ascent of the Rockies’ highest peak, Mount Robson) helped write the mountaineering history of the area, leaving their names attached to geological features, mountain huts and municipal buildings.

I made my first pilgrimage to the region by bicycle, from Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1972. I returned the following year by thumb-power, hitch-hiking to Alberta’s eastern foothills, camping along the McLeod River, traversing the Icefields Parkway, between Jasper and Banff, and penning the first in a series of Rocky Mountain Poems (updated with two new additions, last month).

At the end of the seventies, I returned with mountaineering experience and climbing buddy Tom Hocking to follow in Collie’s footsteps, albeit by a more technically difficult route, to the summit of Mount Athabasca. That began a string of visits over the next few years to climb and ski the Rocky Mountain heights and to photograph their beauty. My first published photographs and commissioned jobs stemmed from these journeys.

A couple of decades passed as I gravitated to the Coast Range, then plied the coastal waters of the Salish Sea and Pacific Ocean, by kayak and sailboat.

Returning to the Icefields in 2002, I discovered that routes I’d climbed just over two decades before had been eaten away by climate change. The Athabasca Glacier has retreated 1.5 kilometres since Collie set foot on it. Since I trod its surface in crampons — a mere 38-years-ago — the toe has lost 400 metres. But it is the volume-loss reflected in the lower height of the glaciers that is the most alarming to a grizzled old mountain man like me.

On nearby Mount Andromeda, the extraordinary ice-face known as “Andromeda Skyladder,” which I climbed with Frank Wieler in 1980, the year noted in geological studies as the beginning of accelerated melting, has all but disappeared. What a tragedy to lose such a sublime sheet of blue ice.

In the fall of 2013, I accompanied another retired alpinist, Lindsay Martin, on a whirlwind tour in the vicinity of Jasper and Lake Louise. We broke in our geezer physiques on the hillsides around Jasper, graduating to a hike up from Moraine Lake to the spectacular Larch Valley, where its namesake trees were shedding their orange needles among the first snowstorms of the season. It was my first visit to this high pass above Moraine Lake since 1976.

This time around, Amanda Jones and I drove a circle route up the Robson Valley on Highway 5, visiting friends there in Valemount; to Jasper and a room in the Athabasca Hotel (immortalized along with a beautiful chambermaid in my poem of 1972 🙂 ); down the Icefields Parkway to Lake Louise, narrowly escaping avalanches sweeping down off the pesky Parker Slabs near Mount Athabasca; on to Banff, then over Highway 93 through Kootenay National Park to Radium and the Columbia Valley (my home for a few years), stopping in Nelson for a two-day decompression at the stately Hume Hotel, before a 700km marathon drive back to the coast over more snowbound mountain passes.

My intention from the beginning was to illustrate this winter trip with daily blog posts from the front, so to speak. As it turned out, aside from collating, adding to and republishing the aforementioned Rocky Mountain Poems, keeping my handwritten journal was about as much as I could manage after a day out lugging my camera gear around. To think that I used to do such things on skis, then retire to a squalid tent!

Norman Collie imagined these valleys would develop busy alpine resorts, like Zermatt and Chamonix. Yet, outside Banff and Jasper, the wild Rockies remain relatively well-protected, thanks to a series of contiguous national parks: Banff, Jasper, Kootenay and Yoho, as well as the Mount Robson, Mount Assiniboine and Hamber provincial parks. Further south, Waterton Lakes National Park, which we visited in 2014, straddles the U.S./Canadian border as the Canadian half of the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.

I sprang for an annual park pass on this visit. Since Parks Canada is waiving fees next year to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday, it’s good until 2018. Chances are, I’ll be getting high in the Rockies again soon.

.jpg)