.jpg)

A-38, Blackney, Johnstone Strait, 1989

“We are the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, the Kwak´wala-speaking people. We are eighteen tribes whose territory reaches from northern Vancouver Island southeast to the middle of the island, and includes smaller islands and inlets of Smith Sound, Queen Charlotte Strait, and Johnstone Strait.” — Barb Cranmer, ‘Namgis Nation

.jpg)

Surf’s Up! Ken Lane Heads South

Twenty-eight-years-ago, I kayaked Johnstone Strait, the 110 km (68 mi) channel that divides the northeast coast of Vancouver Island, and the British Columbia mainland. For me, the trip was a kind of “decompression” after two-years labouring in Toronto’s advertising photography sweatshops.

Our group of 4, including Tom Hocking, Gail McGee*, and Ken Lane, paddled south from Port McNeill, along the east shore of Vancouver Island, taking in Telegraph Cove — a sleepy abandoned cannery site just starting to entertain tourism, now a resort complete with golf course — and Robson Bight, with its killer whale (orca) “rubbing beaches.”

The prevailing wind and waves pushed us southward under a blue sky. Spouts of vapour on the horizon identified a pod of the great “blackfish,” who were soon all around us.

I pulled my Nikon FM camera fitted with MD12 motor drive from its waterproof box, to make a series of photos as a large male (identified later as then-19-year-old Northern Resident A38, Blackney) porpoised by, eyeballing me from not more than 5 metres away.

The rolling waves and wind that were so much fun on the way down pinned us for a day on a beach south of Robson Bight. We ventured onto the water only to play and practice our anti-capsize high-brace stroke in the surf. From the beach, we watched a flotilla of fishing boats, followed by gyres of squawking gulls, bucking the weather as a government-sanctioned “opening” gave them a chance to fill their holds with salmon.

A day later, calm weather made for a comfortable east-west crossing of a glassy, blue passage, until we hit a strong current between Harbledown and Hanson Islands, complete with dancing clapotis waves that tested our high-brace skills to a more uncomfortable degree than the previous day’s dalliances.

After a night on Hanson Island, we paddled through Blackfish Sound to Alert Bay. The village is situated on the west coast of Cormorant Island, just 4.9 km long, and 0.8 km wide at its narrowest point.

.jpg)

Gail McGee and Ken Lane, Hanson Island Camp

More than half the residents of the village are indigenous people of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw — who speak Kwakʼwala. The ‘Namgis First Nation, with 600-750, comprise the largest population on the island.

Passing the impressive throng of totems at the original ‘Namgis Burial Grounds, on the south end of the bay, and the remnant fishing fleet not participating in the aforementioned opening, we landed near the U’Mista Cultural Centre, the attraction that draws most visitors to the island.

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the indian festival known as the ‘potlatch’ or in the Indian dance ‘tamananawas’ is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment ….” ―Dominion of Canada anti-potlatch proclamation, issued in 1883; enacted January 1, 1885.

Opened in 1980, the museum houses the repatriated Potlatch Collection of ceremonial regalia confiscated by Canadian authorities following an 1885 ban on the potlatch ceremony in an attempt to “integrate” First Nations into the dominant settler culture. These extraordinary works of art, the spiritual expressions of their culture, were then sold off as curios to the far corners of the earth, to museums and private collectors. The potlatch law was not stricken from Canada’s books until 1951.

Adjacent to the U’Mista Centre stood another imposing reminder of Canada’s plan to erase aboriginal culture: St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. The brick edifice, decrepit and austere, had lain empty since its decommission in 1974, but for a few attempts at making it useful to the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw as a carving centre. It briefly housed a night club.

But the horrors that many First Nations children endured within its walls, under the purported “care” of the Anglican Church, could not be erased. For many residents, its very presence added insult to lasting physical and psychic wounds administered there.

Viewing the powerful, beautifully carved masks and potlatch regalia, while contemplating the injustice of successive federal and provincial governments toward indigenous people, left me with a strong sense of the resilience of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people and their connectedness to this extraordinary marine environment.

A visit to a Chinese restaurant on the main drag, Fir Street, led to one of those serendipitous events that seem to randomly accompany travel: as it turned out, I recognized the server from an establishment I frequented when I lived on W. 10th Avenue, in Vancouver’s Point Grey.

.jpg)

Towards Blackfish Sound (L-R: Tom Hocking, Gail McGee)

Saving the Tsitika

Returning to Vancouver, I met my future wife, Amanda Jones, and we became involved in the campaign to save Robson Bight from logging. Although the “rubbing beaches” of the inlet, where Northern Resident orcas congregate to socialize and use the cobbled beaches as a kind of giant pumice stone, were supposedly protected within the Robson Bight Ecological Preserve, established in 1982, plans for clear-cutting in the Lower Tsitika threatened the area with possible siltation and other byproducts of industrial “forest management.”

The campaign, which included educational video and an art exhibition (Robson Bight, Wilderness Treasures of Land and Sea, Robson Square Media Center, Vancouver B.C.) was ultimately successful, leading to the establishment of Lower Tsitika River Provincial Park.

I vowed to return to Johnstone Strait, and Alert Bay in particular. A few hours was not enough to absorb the history and meet the people of this remote northwest coast community. I wanted to show Amanda this place that had impressed me so much.

Welcome back

It took me twenty-eight-years to return to Alert Bay. In late August, Amanda and I made an unplanned crossing by ferry from Port McNeill, after a desultory hour or two in Port Alice, where I photographed the languishing industrial infrastructure of the town’s pulp mill, decommissioned in 2015.

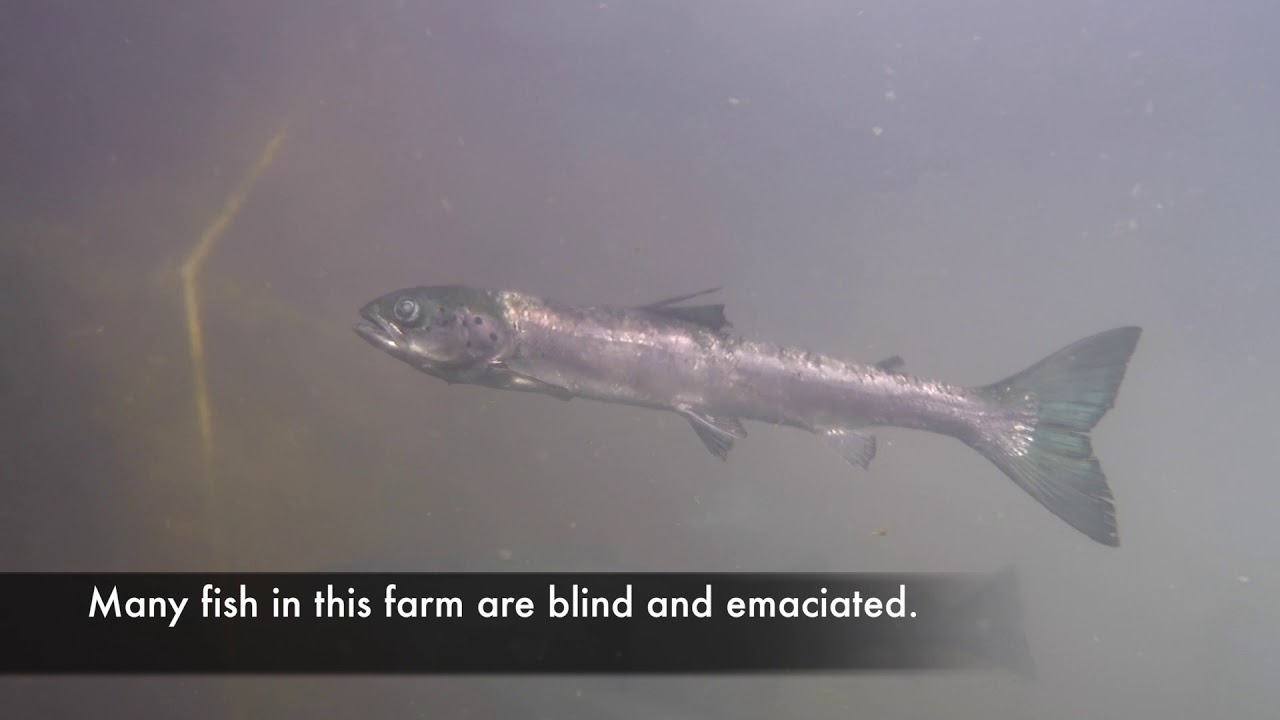

As we disembarked at Alert Bay, on August 23, we were met by a protest. A small group danced and held signs aloft condemning marine aquaculture, or fish farms, commonly seen as the latest threat to the area’s declining wild salmon and the ocean environment in general. More than 20 of these feedlots, raising mostly Atlantic salmon, are scattered throughout the traditional territories of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw.

Biologist Alexandra Morton, long a thorn in the side of the salmon farmers, was among the group, along with Hereditary Chief Ernest Alfred, from the ‘Nagmis, Lawit’sis and Mamalilikala Nations.

Morton had, that very day, released a damning video documenting conditions in open net pens, collected throughout local waters by Hereditary Chief George Quocksister Jr., 68, from the Laich-Kwil-Tach Nation.

Surreal coincidence

“Today, it’s above all the visual art of the red man that lets us accede to a new system of knowledge and relations.” —André Breton, 1946

We made a beeline for the U’Mista centre, where we viewed the aforementioned regalia. A sign, which I believe did not exist on my previous visit, because I made many photos, forbade photographing the sacred objects.

The collection had expanded over three decades. One of the most fascinating pieces, a ceremonial eagle frontlet, had made an extraordinary journey.

In 1964, with proceeds from the sale of Giorgio de Chirico’s 1914 painting The Child’s Brain, Surrealism’s founding father André Breton acquired the headdress. It is well known that Surrealists were greatly influenced by native art. I was aware of their respect for African carving, for instance. But I had no idea until now that they enthusiastically collected aboriginal art of the Northwest Coast.

Below the glass case where the carving now resides, a photo of Breton’s study shows it prominently displayed on his desk. In his last days, Breton seemed obsessed with the mask, staring at it for hours on end.

In 2003, Breton’s daughter, Aube Elléouët-Breton, travelled to Alert Bay to return the headdress and bestow a $40,000 donation. A ceremony was held in the Big House.

Surviving an arson attack in 2013, the collection at U’Mista remains one of the most important representations of the extraordinary artistic and cultural heritage of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw.

Outside, down on the beach, I met Dawn Cranmer. It was her grandfather, Dan Cranmer, who in 1921 held the great potlatch in defiance of the government’s anti-potlach law. The ensuing raid led to the arrest of forty-five people and confiscation of ceremonial regalia.

The hated residential school building, finally razed in 2015, no longer shadowed the U’Mista Centre.

Traditional medicine

We camped under the stars that night, after walking along the waterfront as a beautiful sunset unfolded, casting an otherworldly light on the ‘Namgis cemetery poles.

Our milk had soured in the small cooler we carried, so first thing next morning I drove back down to the Bayside Inn, where we’d eaten supper the night before, to buy some milk.

The protest group again greeted arriving ferries.

We joined Dawn Cranmer at the U’Mista centre to attend her ethnobiology lecture. A small gathering of tourists tasted balsam and devil’s club teas and rubbed aromatic spruce balm into arthritic joints.

Prelude to direct action

A coffee break at Culture Shock Interactive Gallery introduced us to owner and filmmaker Barb Cranmer, whose work we had viewed earlier at the museum.

As we readied to leave, Ernest Alfred was preparing to lead the peaceful occupation of Norwegian-owned Marine Harvest’s facility at Swanson Island, a protest that is ongoing as I write.

To this date, the recently elected Green/New Democrat coalition provincial government have not taken a firm position, despite a pre-election promise made at the Alert Bay Big House to remove pens from the open ocean.

Endangered species

Meanwhile, the Southern Resident Killer Whale live on the brink of extinction, their once-abundant food source, Pacific salmon (primarily Chinook), in steep decline. Last week, a drone-assisted photographic survey joined many other studies that observe starving whales. Last year, the pod’s matriarch died. Granny (J-2), was estimated to be 105.

The most recent data (September 23, 2017) puts the southern residents population at 76 individuals. That number is not much different than when I paddled Johnstone Strait, in 1989. However, their number has declined sharply from a high point of 98, in 1995, prompting governments to list them as an endangered species. Their health is threatened by the combination of bacterial and chemical pollution, interference by boat traffic, and, as mentioned, scarcity of food.

The Northern Residents, of which A-38, Blackney, is a member, is faring somewhat better, with a population somewhere just under 300. Scientists speculate that the larger population and wider range of this clan have so far worked to its advantage. But, just like Southern Residents, they also have an almost exclusive diet of Chinook salmon.

Return to Victoria

Back in the city, I follow news of the Swanson Island occupation. Tents are replaced with more permanent shelters. Another has sprung up on nearby Midsummer Island feedlot, led by members of the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw.

In Victoria, on August 31, I photographed a demonstration at the BC Legislature, with Chief Quocksister in attendance. Occupiers of the farms have pledged not to leave until open net pens are removed from their territories.

Last Thursday, 50 protesters occupied the Saanich constituency office of Minister of Agriculture Lana Popham, who consequently promised to meet First Nations, along with Premier John Horgan, “in a couple of weeks.”

Again, I feel the pull to bear witness to history. Today, (Sat. Sept. 30) witnesses have been invited to gather at Swanson Island. Home commitments preclude my attendance. Perhaps this story might serve, for now, as my contribution.

More info:

*Respected human rights advocate and environmentalist Gail McGee died in 1993.

Project Heart—Honouring Residential School Survivors (video)