.jpg)

Beam me up, Scotty! (IMRT)

In 2003, a battle with cancer forced me to shut down my commercial photo studio. A course of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (I was one of 6 original Guinea pigs for IMRT in British Columbia, now used routinely for the treatment of head and neck cancers) left me gaunt and exhausted, weighing less than 45 kilos (100 pounds). As autumn set in, it wasn’t yet clear if the crab had been vanquished.

The photography business itself was in a turmoil as the digital revolution upended the status quo. Personally, I wasn’t convinced that digital photography made sense for me. Certainly, this upstart development did not equal the quality of film.

As the 21st century dawned, there was no way I could rationalize the $5,500 USD entry fee for the 2.7 megapixel Nikon D1 (to put that in perspective, the recently-released 45.7 MP Nikon D850 lists at $4,300 CA). My process for making digital photos for websites followed the laborious route of scanning prints on a (Plustek) flatbed scanner, edited, as I recall, with PaintShop.

From BC Cancer Agency’s Island Update Magazine

Not that these mundane affairs impinged on my thoughts as I lay, day after day for a month, pinned to the medical linear accelerator, receiving millions of volts of tumour-killing photons (which, going on the medical illustration to the right, turned me into a little green Michelin Man).

But, as I struggled to recover from the devastating effects of cancer, or rather the crude but effective treatment that extended my life, I figured there wasn’t anything to lose and decided to buy an expensive new toy.

Nikon had not long released the prosumer D100, selling for around $2000. Meanwhile, Fujifilm had the FinePix S2 Pro, based on a Nikon F80 body. This meant I could use my existing collection of Nikkor F-mount lenses. Comparison shopping, I was impressed (though what did I know about this new-fangled technology?) by its 6.17 megapixel sensor. The “Super CCD,” with photodiodes oriented diagonally, could apparently produce an image equivalent to 12.1 MP, using a revolutionary interpolation system.

By this point, I had also invested in a dedicated 35mm film scanner (Canon FS 4000) and the printer that arguably made inkjet prints respectable: the Epson 2200.

With accompanying software, including tethering, I put down over $4,000 CA for the S2 Pro. The learning curve was steep, perhaps due to my compromised condition. After all, my head had just been nuked.

The S2 served as a sort of digital post-treatment therapy insofar as it kept my mind occupied and away from compulsive meditation on the frailty of mortal existence and discomforts —the “new normal” my oncologist encouraged me to think of them — left in the immediate wake of my nuclear summer.

As a cancer survivor, twice over now, you might imagine I don’t miss the darkroom with its toxic potions. I certainly prefer working in my “lightroom” with its cheerful, gallery lighting and a few nostalgic icons from the old wet lab.

.jpg)

Tethered Selfie in a Motel Room, 2003

The downside to this brave new world of pixels is the continuing, associated expenses and frustrating, regular breakdowns. I pine for the days when you could buy a camera — used or new — and expect it to last for a decade or more. Sure, film and chemicals were expensive, but nowhere near the cumulative cost, not to mention aggravation, of buggy software. Without naming names (need I?), there seems no end to the schemes devised by photo software developers to part consumers from their money, monthly.

That being said, never has there been more creative opportunity in the field of photography. Though I occasionally shoot a roll of film (truthfully, I haven’t done so in nearly three years) I don’t see myself (re)joining the #filmisnotdead craze. In any case, most new film initiates scan their negs (so do I), and many of those images never get beyond social media. That is, they never make it to print.

Aside from a recent hankering for a Polaroid camera, I rather enjoy processing digital files, at least when hardware and software cooperate. I also value the opportunity to share my work world wide on the web. But I retain the perspective of an analog photographer: that no photograph is complete until it is made into a print.

The photograph at top represents pretty much the last roll of film (Fujifilm RHP-III 35mm Fujichrome Provia 400F (pdf) I shot before I bought the Fujifilm S2. I set up the tripod and Nikon F90X camera in the treatment room at BC Cancer Agency’s Vancouver Island Centre in Victoria, focussed the 24mm lens and estimated exposure, then left it to my wife to release the shutter, before everyone ducked behind the lead wall.

The strange device is about to circle my noggin, projecting radioactive beams shaped by tungsten “aperture” blades. A 3-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan mapped the tumour as a basis for controlling the parameters of the radiation. Infrared markers align the treatment. You might say that the resulting self-portrait illustrates my visceral initiation into the wonders of digital medical imaging.

The photo, and others made in the shielded control room, became illustrations for IMRT media presentations, following digitization with the CanoScan.

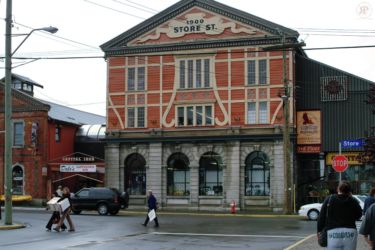

The following gallery contains a selection of photographs made with the S2, which still look mighty good for a 6 megapixel camera … or was it 12? It begins with photos from the first foray outside my convalescence bed, a 98 pound weakling “taking the air” on the streets of Victoria, to action and product photographs as I returned to the bicycle trade and long-distance cycling (randonneuring).

I sold my therapeutic old friend about three years ago for $250, along with a 1GB IBM Microdrive (the S2 was unusual in having dual media slots — for SmartMedia and Compactflash type II (IBM Microdrive compatible). I threw in a Nikkor 35-105mm f/3.5-4.5 AF-D zoom lens.

Last Saturday, as I compiled these images, another one of those strange coincidences occurred that arise from time to time in the life of an archivist. Editing the nice photograph of greengrocer Te-Shun (I noted his name with the S2’s built-in audio recording function that created attached WAV files), I discovered during addition of metadata that I had made the photo exactly 14-years previously, on October 21, 2003.

Susan Carrick - thank you for sharing your story. We are thankful that you are still with us. Enjoying the photos, love the one of the fellow trying to stop as you were taking a photo of the Fairfield Bike Shop….the Mad Hatter is great, such joy in his face…snowdrops are a favorite. Wish they’d grow in my garden!October 26, 2017 – 3:02 pm

Raymond Parker - My pleasure, Susan. Our stories are all we have at the end of the day, and all are treasures, carrying details that we can never know in our own lifetimes how important. Therefore, we should tell them while we can.October 28, 2017 – 12:08 am