.jpg)

Vidal Alcolea, Artist, Toronto, 1987

“When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers?

I would like to sleep, in order to surrender myself to the dreamers …” Manifesto of Surrealism

.jpg)

The birth of Surrealism

In my teens, I discovered Salvador Dali. His work — paintings, sculpture, and collaborations with photographers — spoke to me like no other art.

Soon, I discovered his contemporaries, members of the Surrealist “Centrale” that included photographers André Kertész, Brassaī, and Man Ray.

I was particularly taken with the work of Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Paul Delvaux, and André Bretton, the acclaimed “father” of Surrealism.

Their manifesto accorded with my views conceptually — I’d been devouring the writings of Freud and Jung — but also on a more visceral level, because I’d always had a rich dream life, with enough colliding symbolic debris to keep a depth psychologist busy for years. As it was, I busied myself turning subconscious dream material into poetry.

The unexpected

I found kindred spirits in Vancouver poetry circles, meeting in decrepit pubs and bohemian coffee houses in the Downtown Eastside, rubbing elbows with alumni and faculty of the University of B.C.’s Creative Writing Department … pretty heady stuff for a kid who just scraped through high school.

I found kindred spirits in Vancouver poetry circles, meeting in decrepit pubs and bohemian coffee houses in the Downtown Eastside, rubbing elbows with alumni and faculty of the University of B.C.’s Creative Writing Department … pretty heady stuff for a kid who just scraped through high school.

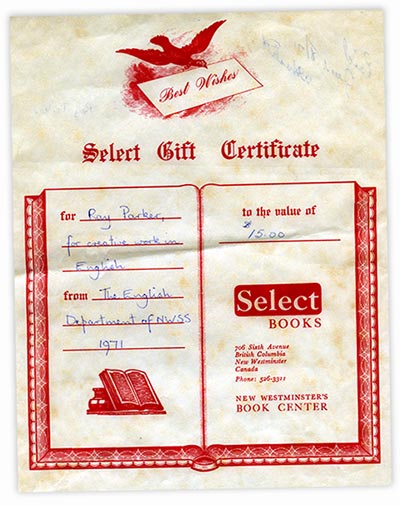

As a sort of consolation prize for my otherwise lacklustre performance in grade 12, I was presented at graduation (a ceremony I did not attend) with a book store gift certificate in the amount of $15.00 “for creative work in English,” the only subject at which I excelled. I put it towards a book I’d been coveting for some time: the sumptuous hardcover, Dali, published by Abrams.

Melmoth Group

Prior to my journey by bus to Toronto, I’d been hanging out with Vancouver’s neo-surrealists, the Melmoth Group that included father and son artists Ladislav and Martin Guderna, Lori-Ann Latremouille, Ed Varney, Sheri-D. Wilson, Gregg Simpson, and poet Michael Bullock, for whose Surrealist novel, The Story of Noire, I provided a cover illustration and author’s portrait.

Days of wine and Clovis

“Once there used to be many people

sitting around the cafe table drinking and smoking

and talking all kinds of nonsense.

It was good.

It was beautiful.” ~Vidal Alcolea, I Will Drink No More Forever

In addition to the Surrealist luminaries listed above, I was also delighted by the overt irreverence of Clovis Trouille — so much so that I obliquely referenced his painting Oh, Calcutta! Calcutta! in a 1973 poem.

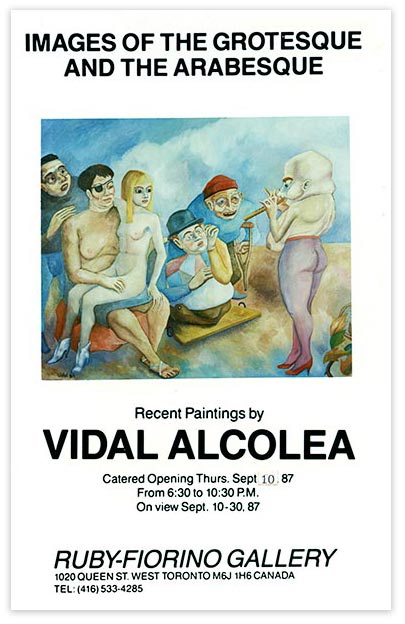

I came upon Vidal Alcolea’s work in the Ruby-Fiorino Gallery while exploring my new neighbourhood, after moving across town, from Christie Pits to Queen Street West.

I saw in Alcolea’s large paintings “of the grotesque and the arabesque,” intended or not, something of Trouille’s disquieting provocation.

Vidal and I sat in a room behind the gallery, drinking wine. I vividly recall the filtered light pouring through the window in the small, cluttered office. He insisted I attend the opening, where more wine and animated conversation was shared.

I don’t know if Vidal considers this period of his work to be in the Surrealist tradition (his later work, I’d say, is more impressionistic) but they certainly evoked a sense of dreamlike fantasy, from the whimsical to the nightmarish.

The Spanish-Canadian artist was also an established playwright with a couple of Toronto productions to his credit when I met him. As we see, he has penned some moving poetry.

We met several more times at Queen Street bars, sharing philosophical and political views and goodness knows what other kind of nonsense.

It was very good indeed.

The lost years

I lost track of Vidal and his work after I left Toronto, until three-years-ago I discovered an Internet trail: auction records for some of his canvases and personal blog entries, including his “Poetry on Dialysis.”

In the same way that social media synchronicity has reconnected me with other long-lost friends, sharing my photo on social media accompanied by the complete poem quoted here led to a reunion of sorts.

Except Vidal had stumbled on the Instagram post and, regrettably, thought comments there, complementary of my portrait and Vidal’s poem, indicated people assumed he’d slipped off this mortal coil. He wanted me to know that, despite health struggles, he was very much alive.

I apologized for the misunderstanding, and in the rapprochement via Messenger we agreed it was nice to reconnect.

The persistence of memory

Some dreams are so convincingly “real” that the transition to waking life is tentative. I have a recurring dream that I’ve returned to high school as an adult to complete the subjects I failed. My subconscious has gathered around the story such a constellation of alternate chapters, so to speak, that the fear I’m going to miss class persists right through morning ablutions.

Thirty years on, my Toronto memories feel like that — a persistent, lucid dream. Were it not for these artifacts and confirmations from old friends that yes, we did do all that crazy shit, I might believe it all a figment of my imagination.

“… all that does not spring from tradition is plagiarism.” ~Dali