Passing Trolley Bus, W. 10th Avenue, Vancouver, 1985

“Photography is an imprint or transfer of the real: it is a photochemically processed trace casually connected to that thing in the world to which it refers in a way parallel to that of fingerprints or footprints or to the rings of water that cold glasses leave on tables.” L’Amour Fou: Photography & Surrealism, p.31

Back from the future

I’ve recently returned to processing more photographs drawn from my archive of negatives made in Vancouver, in the nineteen-eighties — you may already be familiar with the resulting “Eighties Vancouver” gallery — and to the journals that document the daily affairs that accompanied the making of those pictures.

It’s been somewhere around three years since I began the project to revive these photographs in digital form — a finicky, laborious process I do my best to avoid. Along the way, I’ve produced and exhibited a number of limited edition prints, as well as a couple of high quality lithographed posters (for sale at preceding links).

It’s impossible to view these images, from my point of view, without recalling the circumstances of my life that inspired them. While these peripheral facts may not, and should not, have any bearing on the viewers’ perspective, they help me reconnect with my original intent, as much as I’m often embarrassed by the content.

Inspiration

As recounted in a recent post, my photographic aspirations and ventures were in no small part influenced by the great photographers whose lives and works I followed obsessively.

I consumed magazines and books, attended exhibitions of the works of Manual Alverez Bravo, Richard Avedon, Robert Mapplethorpe, Duane Michaels, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Elliott Erwitt, Imogen Cunningham, and many, many more.

North Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery can be credited with exposing me to many of those masters with a marvellous program of exhibitions, beginning in 1981, when it began to focus full time on photography.

I was lucky to have (wealthier) friends who owned extraordinary collections of vintage prints: Edwardian nudes, hand-coloured Japanese studies, early albumen prints, and works by luminaries like Lucien Clergue and Roman Vishniac, the former producing voluptuous nudes lit by the Mediterranean sun, the latter exposing me to the life of Jewish ghettos in Central and Eastern Europe, before the Holocaust silenced the streets.

What magic and what emotion the camera produced!

Camera lucida

I had read about and was fascinated by the idea of “pure” documentary photography — that is an approach which endeavours to remove the photographer from the equation, leaving a sort of “machine view,” as I understood the concept, without any attempt to influence the viewer with the photographer’s personal projections.

Critics of photography as a legitimate art form have rejected its products as mechanical, devoid of personal content or conscious craft. Anyone with a camera could make the same image! I’ve addressed that argument elsewhere, so I won’t dwell on the debate here.

Looking back now, I see that my Eighties Vancouver photos, at least the medium-format work, very much reflected or embodied my personal outlook. Most of the images were made with my circa 1959 Mamiyaflex twin lens reflex camera, loaded with 120 film, mounted on a sturdy aluminum tripod. Accordingly, they proceed from a formal view, and various degrees of conceptual forethought, or “previsualization” as Ansel Adams put it.

I returned numerous times to a location to get the shot I was looking for — the right weather, the right light, the view I saw in my mind’s eye. In the process, whether I was conscious of the fact or not, I was responding at least in part to my inner visions, which were in turn influenced by my study of historical work and my own psychological temperament.

Diary of the decade

I have briefly touched on my personal circumstances at that time, in posts about individual images from the portfolio (usually collected under the “autobiography” category)

For what it’s worth, I’ll reprise some of the details of my life, relevant to the premise of this post, during the relatively short period I concentrated on the Eighties Vancouver project.

The beginning of the eighties marked the apogee of my foray into the vertical world of mountaineering — the “Great Days” as the famous Italian alpinist Walter Bonatti referred to his accomplishments.

I worked at various Vancouver outdoor stores, including The Great Escape, Carlton Recreation, and Mountain Equipment Co-op, where the need to flee the city into the mountains for extended periods was considered product research. For me, they were critical to my mental stability.

At the same time, my photo hobby began to pay dividends, first as a result of the pictures I brought back from my adventures, then from within the outdoor gear trade itself.

I began shooting catalogue photos for MEC, branching out to individual manufacturers, producing magazine ads. Within a couple of years, I was shooting everything from light fixtures to street fashion. I rented a space to accommodate jobs too big for my makeshift apartment studio. I left MEC, not without some bad blood, but continued freelancing for their catalogue.

I was a real photographer now. And that meant facing real photographer challenges. Like hunger.

Nineteen-eighty-five was typical.

My journals record a continual struggle to cover rents, utilities, photographic materials … and food. As the year began, viewed from my shared apartment on West 10th Avenue in Point Grey, spring cherry blossoms and matching pink neon added the only colour to an otherwise monotone diary of overdue bills and self-recrimination. There was nothing for it but to steal from my roommate’s stash of mescal to drown my sorrows.

The pink neon sign

on the market across the street

blinks once and leaves the evening grey.

Tattered awnings leak

like the weary memories

that stain the pages of this book.

Late night moviegoers

wander onto the all too common

greyness of the street

where green streetlights offend

lovers strolling happily below.

A face turns slowly upwards in a trance

through the oily yellow mescal in my glass

A solemn thunder in the hills beyond

the cloistered streets.

Goodnight, garish dreams, goodnight.

Summer bought some reprieve. A long stretch of sunny weather. Nude sunbathing on Wreck beach. The proceeds of another Co-op catalogue and a sideline: selling beauty products to hair salons, or “designers” as they now preferred.

However, two roommates left for Toronto at the end of August, with the result that rent doubled (to $200 ea.) for my girlfriend and I. At least we now had our own bedroom.

The Christmas of ’85 was particularly harsh. The bad weather was one thing — one of the coldest winters on record — but my financial situation was dire. The cupboards were bare. My lover had fled my dark mood to attend a party. I couldn’t afford Christmas presents.

Despite my melancholic disposition, those days were not all unhappy. There were dinner parties and dancing (when the money came in). The deep freeze of November, 1985, led to my last “serious” climbing adventure: I teamed with fellow photographer and graphic designer David Harris to make the first ascent of a steep rock fissure and vertical slab of water ice on the brooding north face of the West Lion, which we named “Advertising Executives in Space.”

Though exhibitions of my work drew little attention, I persisted in the conviction that the photographs I was making, outside of light sconces and camp stoves, were in some way important.

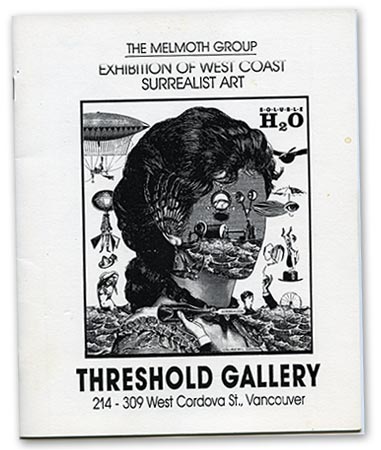

Inspiration came from friends and acquaintances within the larger Vancouver arts community. I associated with a circle of West Coast Surrealists also known as the Melmoth Group.

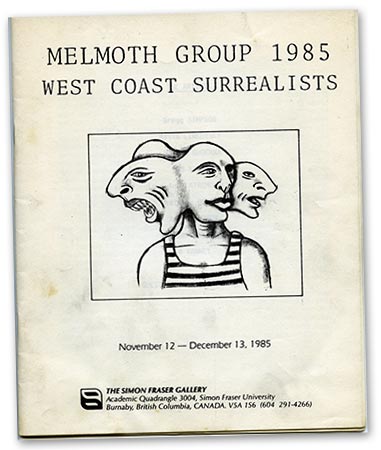

In the depths of that raw winter of ’85/‘86, I attended several gallery openings, from Vancouver to Washington State. A journal entry dated November 19, 1985, makes note of the West Coast Surrealists Show at Simon Fraser University. On a “bitterly cold” evening, I transported Martin Guderna, his sister, modern dancer Catherine Lubinsky and my girlfriend to the show in my Chevy van (a vehicle which endeared me to artists creating larger canvases) to the campus atop Burnaby Mountain.

In the depths of that raw winter of ’85/‘86, I attended several gallery openings, from Vancouver to Washington State. A journal entry dated November 19, 1985, makes note of the West Coast Surrealists Show at Simon Fraser University. On a “bitterly cold” evening, I transported Martin Guderna, his sister, modern dancer Catherine Lubinsky and my girlfriend to the show in my Chevy van (a vehicle which endeared me to artists creating larger canvases) to the campus atop Burnaby Mountain.

As you can see from the cover of the catalogue at left, the show ran from November 12th to December 13. It featured the works of group members Greg Simpson, Assia Linkovsky, Martin Guderna, his father Ladislav, Ted Kingan, Lori-Ann Latremouille, Ed Varney, Andrej Somov, and Michael Bullock.

I was particularly taken with the work of Ted Kingan, whose surreal landscapes — or “inscapes” as they were called — evoked “both the ocean depths and mountaintops at the same time,” reminding me “of a legend that says from the summit of a high and holy mountain your shadow is cast across the land beneath, revealing … the way you should go … as in a dream.”

I also took note of Ed Varney’s whimsical collages. Unbeknownst to me at the time, Varney employed an English nanny, my future wife, Amanda Jones. No dream, however surreal, could have anticipated that my circuitous route, via Toronto and back to Vancouver would lead to the place I am now? Varney, who we lost track of for a while, also ended up on Vancouver Island. When Amanda and I discovered we had Ed in common, we also realized that we had been at one of the Melmoth Group’s openings in Gastown — the one represented by another catalogue from my archive, above right.

Lori-Ann Latremouille, her playful charcoal drawings inspired by dreams, lived just up the street, where I occasionally shared a darkroom owned by her boyfriend, Michael Wrinch. Poet Michael Bullock also lived in Point Grey and I made his portrait and the cover photo for his erotic surrealist novel, The Story of Noire.

.jpg)

Escher’s Arch

“The mere fact of photographic transposition means a total invention: the capture of a secret reality. Nothing proves the truth of super-realism so much as photography.” ~Salvador Dali

Dream machine

It might seem that my interest in surrealism was at odds with my own tightly-controlled documentary-style of photography — “straight photography,” as some would have it. Yet, I considered the camera itself as a kind of dream machine. I regarded the whole process, from the physics of light bent through time and polished glass, projected onto light sensitive emulsions, to the “laboratory” magic of development and printing, as a kind of alchemical reduction of the “seen” world, which might reveal some precious, secret reality hiding in the dross. This was, as I interpret that animating fever today, the source that drove me out into the cold to conjure up Hostel, Jericho, Vancouver, 1985

“The nature of the authority claimed by [Edward] Weston and Straight Photography is grounded in the sharply focussed image, its resolution a figure of the unity of what the spectator sees … that in turn founds the spectator himself as a unified subject. That subject, armed with a vision that plunges deeply into reality … seems to find unbearable a photography that effaces categories and in their place erects the fetish, the informe, the uncanny.” L’Amour Fou: Photography & Surrealism, p.395

But, barely concealed between the lines of my journal entries, an unwholesome envy lurks. I felt an outsider among these successful artists. Perhaps I didn’t fit the surrealist profile, defined by Ladislav Guderna as “a very happy, optimistic philosophy, a state of mind that refuses convention.”¹ Then again, perhaps I was applying Salvador Dali’s “paranoiac-critical method.”

The photograph that drew the greatest approval from my surrealist friends came about through a mistake — a serendipitous double-exposure made at the same time as Under Burrard Bridge, 1985.

Between writing this “confessional,” I’m reading one of the books given to me last month: The Day Books of Edward Weston, I. Mexico. Between tales of living amidst a revolution, tequila-enhanced gaiety within Mexico City’s arts community and sexual adventures, the celebrated photographer bemoans his perilous financial state — overdue rent, periods of famine between print sales and paying commissions — and, woven throughout, Weston’s resentment of those mundane affairs that impeded complete abandonment to his visions.

¹As quoted by Vancouver Sun writer Eve Johnson, during the “Open Cages” exhibition at Pitt International Galleries, in 1986.

Eighties Vancouver photographs available for sale here, including Passing Trolley Bus

.jpg)